Med student’s life changed by epilepsy, and physician

In a few years, Gabrielle “Gabi” Morris will graduate from medical school, having arrived there, in a way, because of an Easter Sunday when she fainted in her mother’s arms.

And having arrived there because of the doctor who bore her up when she was angry at the hand life had dealt them both: epilepsy.

In the years following their encounters, the patient never forgot the physician whose compassion helped bring her into the fold of medicine, but never knew if she would see Dr. Brad Ingram of Madison again – until she did, at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the place where his star has risen and where she is reaching for hers.

A first-year student in the UMMC School of Medicine, Morris, 22, was a young girl when she learned she had a disorder that can deaden the senses – but which also made her prospects come alive.

“Without epilepsy, I wouldn’t have met Dr. Ingram,” she said, “I wouldn’t have realized that I wanted to be a doctor, and I wouldn’t be sharing my story with others.”

The plot of her story advanced dramatically when she was 10, on a day that celebrates victory over the grave; it buried her hopes instead, or so she believed.

She had just finished enjoying an Easter brunch with her family when her secret came out of hiding.

“After helping clear the dishes, I felt as though I was going to faint,” she wrote in an essay years later. “The last thing I remember was looking at my grandmother's face, unable to respond, while I seized in my mother’s arms.

“I had never felt so helpless in my life.” Afterward, she made her family promise to keep this a secret, telling only her teachers, in case she had an episode at school.

Brought up in Jackson since she was 6, Morris had suffered seizures since she was 8 or 9. Only her younger sister, Sydney, who often slept in the same room with her, knew how bad they were. The first one had come in the middle of the night with her dad, who, believing she was just choking, patted her on the back.

But they got worse. Bruises and bumps and fleeting fears of demon possession disturbed her nights. Sydney would call to her parents for help, but by the time they reached Gabi upstairs, the seizures were over.

During each one, she could see and hear everything around her, but had no command of her body. After falling out of bed, she would convulse on the floor. She couldn’t respond to questions. But she could hear her sister crying.

After witnessing the Easter attack, though, her parents took her to the emergency room at what is now Children’s of Mississippi. They learned she had benign rolandic epilepsy. Her brief seizures were triggered by lack of sleep.

She was diagnosed at an age when driving a car was no distant dream, when the rewards of adolescence, of freedom and control, were like gifts waiting under a tree. Now, her future promised a loss of control, a descent into embarrassment; people would laugh at her. That’s what epilepsy meant to her.

Until she met Ingram. “I was diagnosed with epilepsy at 16,” said Ingram of Madison, a professor of pediatrics-neurology at UMMC. “I felt like my whole future had evaporated.

“I was angry at God. Because there’s no one else to be angry with. You feel like your body can turn on you at any moment. And it takes so much from you.

“You don’t get invited to sleepovers anymore. You can’t drive anymore. You can’t go swimming anymore. It’s one ‘can’t’ after another. Your world gets so small. But you don’t have to stay there.

“In order to live your life with this, you have to process your emotions.”

Which is what he helped young Gabi do. “The first time I met him, he could sense that I was on edge,” Morris said. “I was scared and wondered ‘why did God do this to me?’

“Dr. Ingram had also been angry at God. Whenever I visited him, we talked about this. He gave me peace and made me realize that this is just part of who you are. I wasn’t angry anymore.

“I also realized that, even though he had epilepsy, he was a doctor and was successful, and could use his own experiences to ease my mind. That was huge for me at that age. It sparked a drive in me.

“In that moment, I said, ‘I want to do what he does.’”

Over the course of a few years, the two saw each other maybe 90 minutes altogether – about 15 minutes each appointment. In little more time than it takes to drink a cup of coffee, a doctor’s visit can be eye-opening, Ingram said.

“A patient will remember that 15 minutes the rest of their lives. I remember the doctor who diagnosed my particular type of epilepsy. She changed my life; she gave me hope that I could still do whatever I wanted to do.

“I saw her one time, but I remember everything about her – and that was 1997.”

It’s been some 20 years since Ingram’s last seizure. But he will be on medications for the rest of his life. “I’m fine with that,” he said. “It’s worth it to be able to drive and do the things I like to do.”

Medications helped Morris too. “Dr. Ingram told me I could do anything I wanted as long as I stayed on them,” she said. And she did: soccer, basketball, volleyball, cross country.

Epilepsy did not stop her; it motivated her, as it had motivated Ingram: to pursue the call they couldn’t resist.

On Morris’ medical school orientation day in August, Ingram’s smile and words were still with her. Her seizures were not.

By her early teens, the episodes had disappeared, but their influence endures. Morris shares her story publicly now and anticipates the day when she can help her patients meet their own struggles – and prevail.

But she did not foresee meeting Ingram again.

“On orientation day, I heard that a ‘Dr. Ingram’ would be speaking to the M1s,” she said. “I wondered, ‘is that him?’”

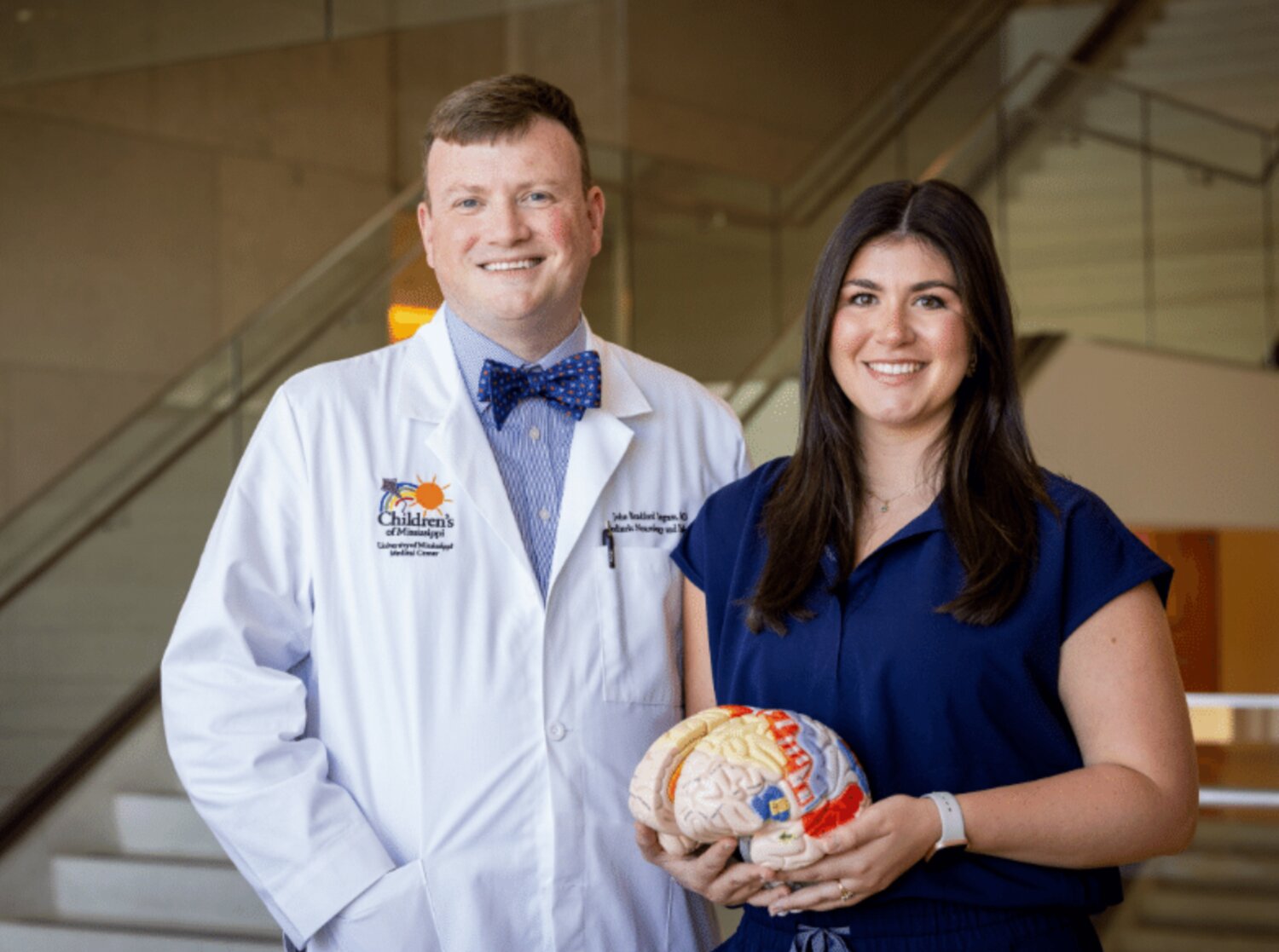

Before his talk to the first-year medical students, as Ingram recalls, “this radiant young woman comes up to me and says, ‘You don’t remember me.’

“But, whenever there’s an interesting diagnosis and intense conversations – those patients I will never forget,” he said.

In fact, he remembered Morris’ entire family, especially her mom, who “reminded me of mine,” Ingram said. “Because of how worried for their child both had been.

“I always looked forward to seeing Gabi’s family; they were formative for me.” As he had been for Morris.

“At orientation,” she said, “I told him that, without him, I wouldn’t be here today.”

Ingram believes Morris will be “an amazing physician, a rock star”– in a future he helped ignite. Which is perhaps another reason her words touched him so.

“I have to admit, she wrecked me,” he said. “I was barely able to give my talk. What she said was such a gift and out of the blue and so kind.”