Herring’s book offers insight into political history

The Switcher: Jim Herring and Two-Party Politics | The unique perspective on a transitional time in Mississippi politics by the only former member of the Mississippi Democratic Party State Executive Committee to later serve as Chairman of the Mississippi Republican Party. The author, Jim Herring of Canton, takes the reader through his political activity as a Democrat from the mid-1950s up into his switch to the GOP during the first term of President Ronald Reagan and then provides a behind-the-scenes look at his work as state Republican Chairman from 2001 to 2008. Part family history, part memoir, part political recollection, the text benefits from the work of Joseph L. Maxwell III, whose previous research and writing in books by Republican leaders Wirt Yerger, Billy Mounger, and Charles Pickering provides context for the personalities and history in the book. A book signing is set June 6 at Lemuria.

The beginning sets the stage as 17-year-old Herring experiences a gubernatorial debate in 1955 Canton, moderated by a local attorney and former state senator, also his father, George Bryan Herring. Fielding Wright, Mary Cain, Ross Barnett, Paul Johnson, Jr., and J.P. Coleman – Democrats all - discussed the issue of the day: segregation. Herring’s family introduced him to politics and provided connections to the politicians who would rise to power. His uncle was college roommates with John C. Stennis; his future father-in-law was college roommates with Jim Eastland; his father was Bill Colmer’s law partner and then in the state Senate a close ally to Governor Mike Connor. His recollections of family, friends and events would be familiar to his peers in Canton, Jackson, and the University of Mississippi from the 1940s through the 1960s.

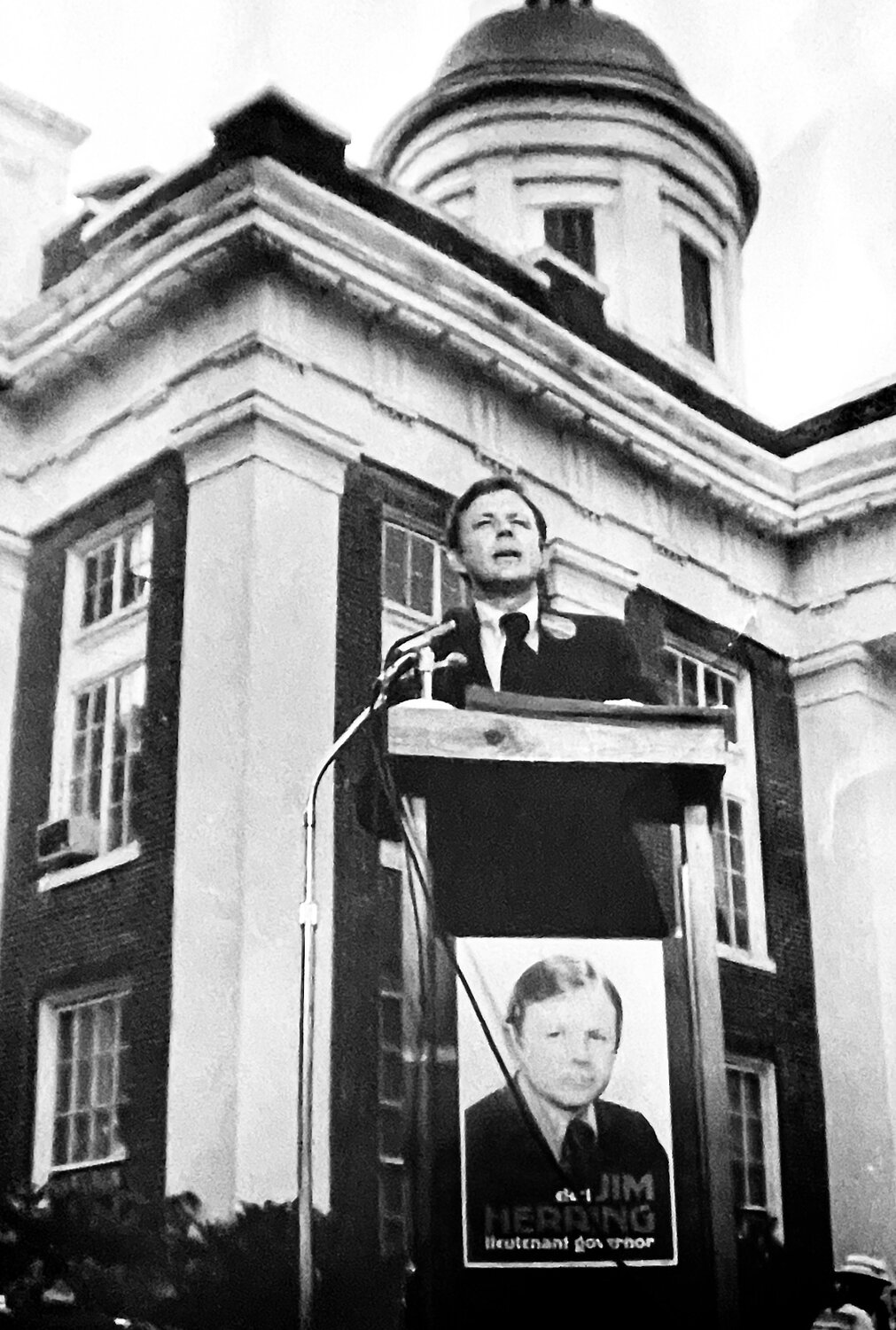

After college and his military service as a JAG officer, Herring returned to Canton and won the position of county attorney. As a prosecutor, Herring forged a relationship with the District Attorney, Bill Waller, Sr., which would impact his future political decision. Later, Herring himself won the District Attorney position. In 1974, as now Governor Waller neared the end of his term, he encouraged Herring to consider a run for Governor in 1975 as a counter to William Winter, whom Waller suspected would run. Herring began to test the waters and when he called Waller to say he was running, Waller told him he was instead backing a different district attorney, Maurice Dantin, but that Herring should run instead for lieutenant governor. In the governor’s race, Waller saw the defeat of Winter he wanted, but not by his candidate Dantin; Cliff Finch won the Mansion. Herring came up short for lieutenant governor, placing third behind Brad Dye and eventual winner Evelyn Gandy. The chapters on Herring’s 1975 race and 1979 contest for governor (won by Winter) provide the flavor of 1970s Mississippi politics as the stump speaking, alliances, and machinations of power brokers met the new public relations and advertising era of campaigning.

Throughout the book, Herring’s knowledge of Democratic Party players gives insight into the squabbles in the party leadership, from the power struggles between Black and white factions; through a party whose chairman stood in open opposition to the sitting Democratic governor; into more recent years as the Democrats purged leaders and officials who would not, in the party’s eyes, demonstrate sufficient loyalty to the party. He quotes former governor Ray Mabus speaking at a Democratic state convention, “If Democrats formed a firing squad, we’d do it in a circle.” As much as ideology, Herring seems to suggest, this intraparty chaos spawned more and more “switchers” like himself.

By 1984, Herring stood on stage in Gulfport as part of the organizing committee for a campaign visit by President Reagan. In 1987, he ran as the Republican nominee for Attorney General, losing to then-District Attorney Mike Moore in the general election. In 1997, Governor Kirk Fordice appointed him to the Mississippi Court of Appeals, a seat he would later lose to Tyree Irving (himself now the current Mississippi Democratic Party Chairman).

The second half of his book relates his role as Republican Chairman in and perspective of the last two decades of Mississippi Republican political fights: the redistricting and tort reform fights leading to the switch of Democratic Lieutenant Governor Amy Tuck to the Republican Party; the 2002 Pickering-Shows congressional race; advancing Black Republicans (Tchula Mayor Yvonne Brown and candidates Daryl Neely, Danny Covington, and Clinton LeSueur); Haley Barbour’s 2003 gubernatorial campaign against incumbent Democrat Ronnie Musgrove; Amy Tuck’s 2003 Republican campaign against Barbara Blackmon; trial lawyer indictments; tobacco fights with Democratic Attorney General Mike Moore; and more. He digs into Barbour’s legislative triumphs over the Democratic legislature with Operation Streamline, tort reform, and Medicaid, as well as the fight over Tuck’s proposed “tax swap” to increase cigarette taxes to decrease sales tax on groceries.

Herring gives much attention to his role on the Republican National Committee and the impact of national elections during his terms on Mississippi politics. Herring viewed his time as chairman as a compromise “middle-ground” option for the various factions in the party and believed his role was to unite the party as much as possible. That theme of balancing purism with pragmatism runs throughout the book and stands as a contrast to – or perhaps as a reaction of – the division and strife Herring left behind in the Democratic Party.

The Switcher provides an important piece of first-hand Mississippi political history overlapping and closing the gaps between Erle Johnston’s Politics: Mississippi Style and Taggart & Nash’s Mississippi Politics: The Struggle for Power. Besides the actual campaigns, Herring pulls back the curtain on internal party politics of both Republicans and Democrats. This account of Mississippi’s transition from the Democratic one-party “solid South” into a two-party (but Republican-dominated) state will interest students of political history.

Brian Perry is a former political columnist for the Journal.